![A. Laurie Palmer. Heap Leach Field, Nevada (silver). Courtesy of the artist.]()

A. Laurie Palmer. Heap Leach Field, Nevada (silver). Courtesy of the artist.

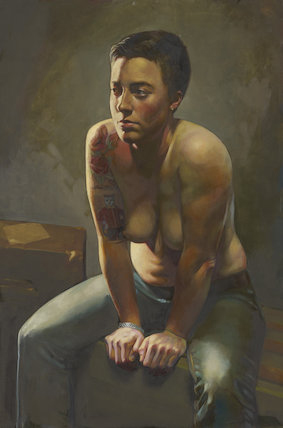

In 2015, Black Dog Publishing released A. Laurie Palmer’s book, In the Aura of a Hole: Exploring Sites of Material Extraction, which documents multiple visits the artist made to sites of industrial extraction around the United States. Describing trips to Texas, Florida, New Mexico, Wyoming, and California, among others, Palmer’s essayistic account weaves personal experience and history, philosophy, science, politics, and economics, revealing the complex and reciprocal relationship between humanity and the materials on which it relies. Palmer is a sculptor based in California; she has exhibited widely since 1988, collaborated for twenty years with the artist group Haha, and cofounded the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials.

Caroline Picard: Can you talk about how In The Aura of a Hole developed?

Laurie Palmer: There were many seeds for this project. One is from the early 1980s, when a friend gave me Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura while I was living in San Francisco. In that philosophical poem, Lucretius asks straightforwardly: What is this place? What is it made of? How does it work? His answers are as helpful now as they were in 50 BCE, in the sense that his curiosity, detailed observations, and empirical imagination still reverberate. He was an early proponent of a DIY ethic: he trusted his own experience to make sense of things. As an Epicurean, he believed the gods and their spokespersons were not authorities to be trusted, while being nevertheless supremely humble, in his desire to hear the opinions of others.

Two thousand years later, the world is materially different—perhaps destroyed, certainly drastically altered—and we now question how certain human practices and ideologies have become naturalized, as if they are forces that can’t be changed, that are part of the nature of things. Lucretius’s direct approach is helpful in a different way for questioning the intransigence of these practices and ideologies, but really it was his poetic imagination and inflamed curiosity that moved and affected me so many years ago. And his willingness to ask simple questions…

![A. Laurie Palmer. Iodine evaporation, Oklahoma. Courtesy of the artist.]()

A. Laurie Palmer. Iodine evaporation, Oklahoma. Courtesy of the artist.

CP: Was the book at all influenced by your studio practice?

ALP: In the early 1990s, while writing about art, making art, and teaching art, I had the idea to write a book about materials that might be relevant to teaching sculpture. I thought I could write a sort of handbook of descriptions and associations; I would write about the world of matter as if it were art. But I didn’t write it because I didn’t think it had any ground. By ground I mean a more located politics, addressing the privatization of space and resources.

I started thinking about land as both abstract space and tangible material and to explore its status as a “fictional commodity”

I found the ground for the book when I began to question land use in my own practice of making. Haha’s work had always been place-based, and that long collaboration is another important seed. But in the late ’90s or early 2000s, I started thinking about land as both abstract space and tangible material and to explore its status as a “fictional commodity,” in Karl Polanyi’s term. This led to visiting mines, where land as space and material becomes explicitly commodified—turned into an object. The question of thingness (what makes a thing cohere) has always been an art question for me, a sculpture question. From 2003–04, I was given the unbelievable gift of time to read and think at Radcliffe College; the experience both opened and unhinged me. It took a long time for me to filter out all the joyful noise, and in the end the book is something different from whatever I had hoped would result. The research that went into it has become a bountiful source for making new projects, and the writing helped me find new ways to think about being in the world. As an artist I want to be changed by what I make, through the process of making it. Working on the book did that. I crafted it as a porous whole, to create a certain picture of the world. Even if it’s unevenly geeky, digressive, personal, or didactic at times, it’s nevertheless a porous whole made of eighteen holes. The golfing analogy didn’t occur to me until after it was published. In my mind, it is an art project because it is constructed more as a thing than a coherent narrative and because that thing consists of different kinds of voices, or of information, which might not exist together except perhaps in the permissive context of art. As in artmaking, I let more in than I could make explicit sense of, with the hope of giving the reader and receiver a lot to work with.

![A. Laurie Palmer. Copper waste piles, Utah. Courtesy of the artist.]()

A. Laurie Palmer. Copper waste piles, Utah. Courtesy of the artist.

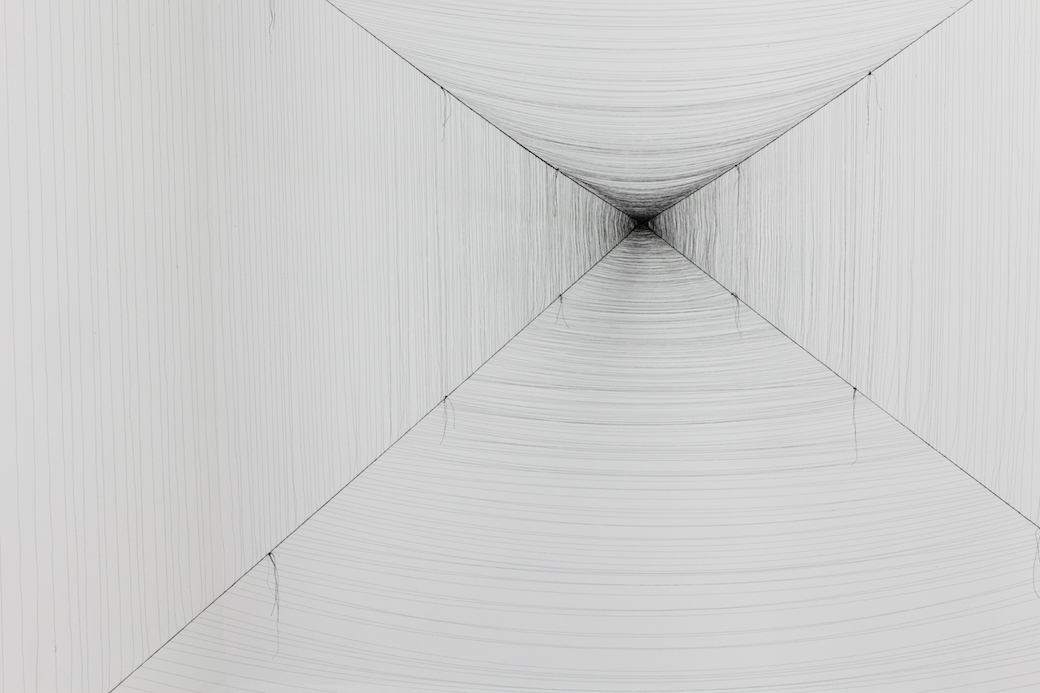

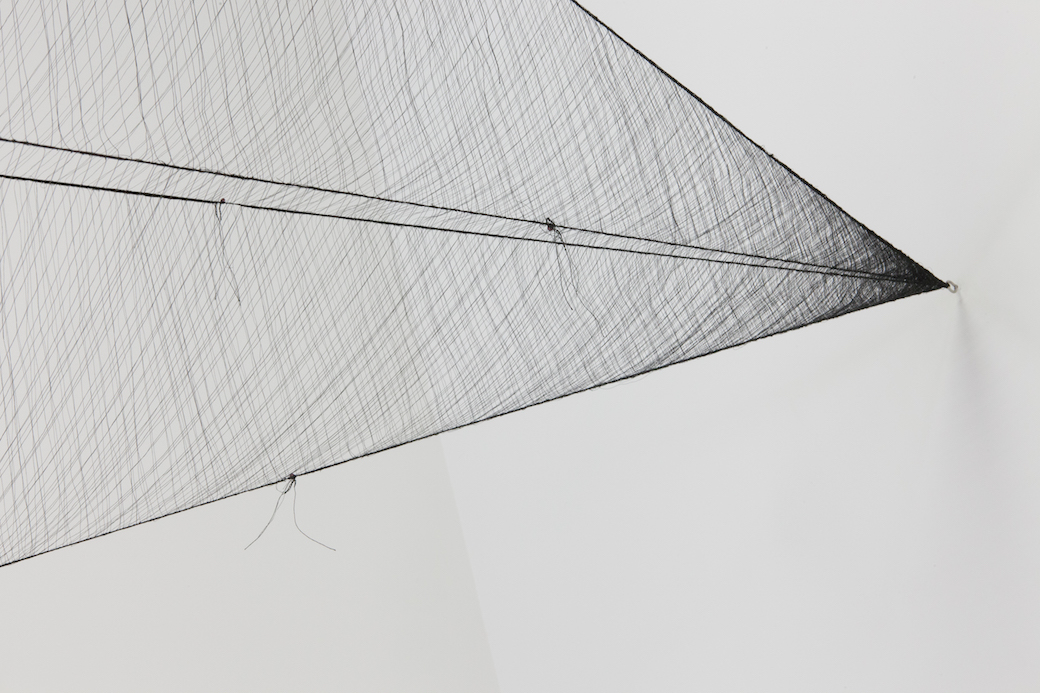

CP: In the introduction, you say you want to break the script, to take a “reparative rather than paranoid approach.” I feel ever more aware of how embroiled I am in systemic violence, in no small part due to the modes of industrial extraction on which my daily life relies. While I recognize that entwinement, it seems like a dead end to simply say, “I will not participate,” partly because it’s impossible not to participate. But I also worry that struggling to maintain a refusal might require so much of my energy that I would end up blind to alternative, nonviolent possibilities. I find that your book stirs up a different kind of awareness, but I’m not sure what to call it.

I think of art as a really big net, with a broad tolerance for contradictory reality.

ALP: I’m not sure what to call it, either. In some ways this project involved digging deeper into a wound—learning more about and specifying my complicity in the interconnected violence you speak about—of ecosystem/world destruction, resource depletion, militarism, surveillance, poverty, racism, and unemployment as necessities of capitalism, and other outrageously wrong systemic priorities, all of which support and perpetuate each other. Alternatively, drawing connections between the materiality of the Earth and our bodies reveals our vulnerability and our complicity in a larger-than-human frame and points to a different kind of connection, to focus on and explore as a way forward. Of course it is facile to say everything is connected, but it’s interesting to try to specify how they are connected. And the closer one looks, the more surprises one finds, creating a picture for which the laws of non-contradiction do not apply! I think of art as a really big net, with a broad tolerance for contradictory reality. With writing, one is always struggling against an exclusive logic, which makes it so hard to write and which makes really good writing so exquisite because it refuses that logic. I would like to be a writer, but I am an artist. But to return to your question: a reparative approach assumes disaster has already happened, is happening, and is ongoing alongside a lot of other things that have happened, are happening, are perhaps not so visible, might come to the surface as useful, could offer the seeds for different understandings…

![A. Laurie Palmer. Silver Mine pit, Nevada. Courtesy of the artist.]()

A. Laurie Palmer. Silver Mine pit, Nevada. Courtesy of the artist.

CP: In the “Iron” chapter, you begin with a quote: “There is enough iron in the body to make a fairly large nail.” I feel like your narrative makes the individual commensurate to these massive systems of commerce, technology, and science, and to the level of atomic material—that you’ll illustrate why metal is strong. How did the scope of these systems envelop you?

ALP: When I visited extraction sites, my body always seemed out of place, in terms of the scale of the excavations, the presence of free-floating toxins, and the machines that would not notice a living thing. And I felt overwhelmed by the sensory details, more than I could make sense of. But I also felt this sensory overload created a link between my body and the place, the material, and the human guides who seemed so engaged with their work. I know that there is a certain idealization involved in this perception, but my guides knew a lot about what they were working with, and this knowledge created an unexpected intimacy with the material and the place, in contrast to the massive and distancing scale of the excavations (and their long-term effects). A friend described my mine visits as “aesthetic encounters.”

In The Ideology of the Aesthetic, Terry Eagleton wrote that aesthetics was born as a discourse about the body—that aesthetic philosophy, as it was developed in Germany in the 1700s, had to account for the body and its sensuousness to allow power, in the form of reason, to maintain control. If it were possible to redefine the term aesthetics for my own purposes, I would rip it open: a capacious process of coming to know that lets in more than we can necessarily make sense of, one that maybe even accesses a certain formlessness, or a version of Michael Taussig’s bodily unconscious. That might sound overwhelming, but it gives us more to work with than what seeps through a finer-grained sieve; it makes room for creative acts of interpretation, for making new shapes with what is latent and immanent. But complexity is incredibly intimidating and humbling, and I found myself identifying with a vole, a blind burrowing rodent, motivated by hunger and an obsessive nature.

![A. Laurie Palmer. Geothermal Resources, Nevada. Courtesy of the artist.]()

A. Laurie Palmer. Geothermal Resources, Nevada. Courtesy of the artist.

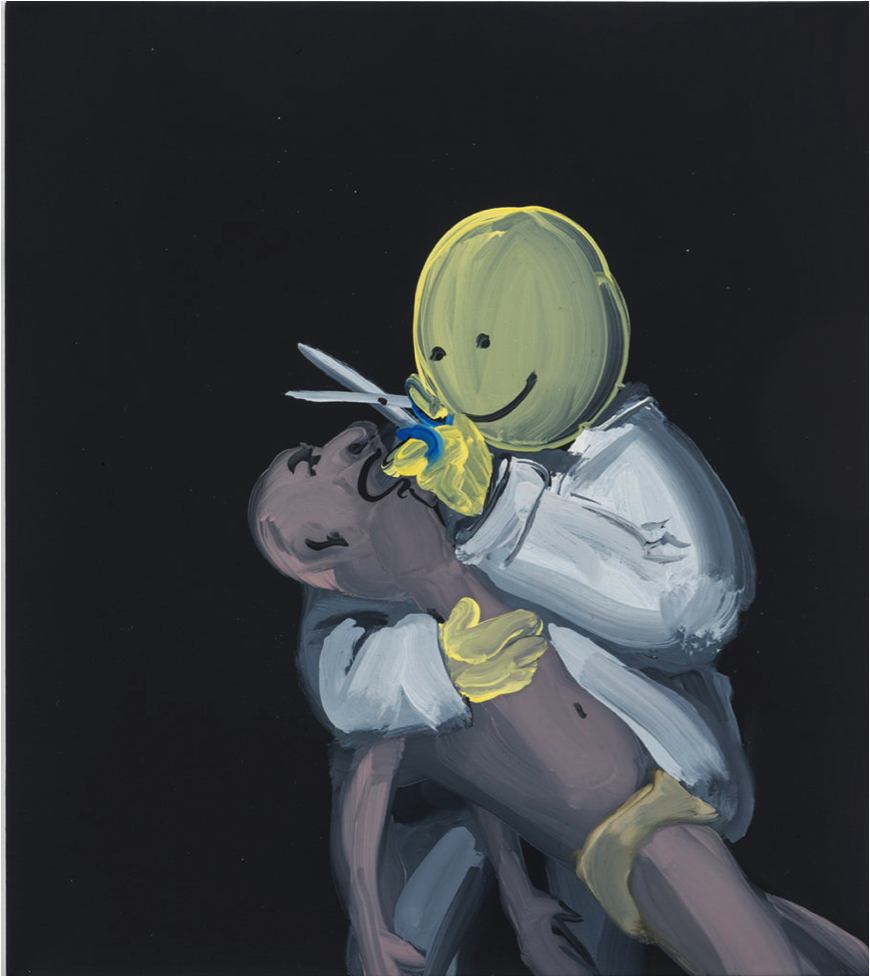

CP: I feel that you are also vulnerable to the logic of these massive industrial sites, maybe especially in the face of those who guide you…

It does seem that most of our destructive human practices are built in defense against a material or bodily condition that we share with other humans and with the nonhuman world.

ALP: What does one do with vulnerability? I think about vulnerability as openness to change. Vulnerability is a kind of potential. Change can happen in any and all directions. Fear and shame are two defenses against vulnerability and desire, against needs that might not be met. Pleasure and connection are effects of opening oneself to vulnerability and the possibility that needs might be met, that one might be recognized. Some might say one first needs to create a secure space to enjoy these effects, or they might say there is a limited supply of resources. But cause and effect are all mixed up in a complex world, and showing vulnerability can also be the precursor to feelings of continuity and connection. I am speaking in dangerously ungrounded abstractions. But it does seem that most of our destructive human practices are built in defense against a material or bodily condition that we share with other humans and with the nonhuman world. I am enamored with Michael Marder’s writing about plants because, among other reasons, he uses the plant/human analogy to expose our vulnerability. Plants are turned inside-out, oriented in their tissues toward the material world, from which they derive all their sustenance, and they are rooted in place, exposed to whatever happens there, where they are. We also derive all our sustenance from the material world and are also in some sense rooted—by our physical bodies and by the Earth’s gravity and specific atmosphere with which we evolved. One can’t sustainably separate a plant from its environment, and now we can’t separate our environment from us. An individual is a working fiction, a thing that has only fictional coherence, imagined boundaries; both fictions are useful but not fixed. The boundaries are subject to change, and even slight, incremental change can help. It is already happening, with contributions coming from many different directions.

![A. Laurie Palmer. Sulfur pile, BP refinery, California. Courtesy of the artist.]()

A. Laurie Palmer. Sulfur pile, BP refinery, California. Courtesy of the artist.